This page is an open forum for you to share your thoughts with colleagues.

Please consider submitting a brief blog with perspectives about our lives in medicine.

Blog anonymously with minimal descriptive information, or with your name.

Submit to pwp@TCMS.com

Submitted February 2026

by Troy Alexander

Connected in Community

We are all recovering from something.

Maybe you are like me, and recovery comes from childhood trauma.

Maybe you were hurt as an adult.

Maybe you are grieving a loss that still catches you off guard.

Or maybe you are fighting battles with addiction—quiet ones, loud ones, or ones we wish we didn’t have to name.

No matter what it is, you’re not alone.

I serve regularly in a local recovery ministry, and every time I’m there, I’m reminded that healing is not a solo sport. We sit together to share our struggles, celebrate the victories (small or large), and try our best to find healthier rhythms. Different stories. Same need to not be alone.

And that’s where community becomes more than a nice idea -- it becomes essential.

Philosopher Dismas Masolo, in his book Community, Identity, and the Cultural Space, described modern communities as “open ended and amorphous,” defined not by who’s in the room but by what the people in that room believe and practice together. I love that thought–you can be part of many groups, yet only some will feel like home.

Take UT football, for example (Yes, I’m going there). I can sit in the same seats every game, surrounded by the same fans. I don’t really know them, but we do share a similar passion for those few Saturdays every year. We all yell at the same refs and cheer for the same touchdowns. For a few hours, we’re united. But at the end of the day, they don’t know me. This is not a community–it is shared enthusiasm.

Community, however, IS where you can take off the mask, even just a little. That is one of the reasons I believe so deeply in the role of the Travis County Medical Society (TCMS). Physicians spend their days caring for others, often without a place where they can exhale, be human, or admit they need support, too.

TCMS isn’t just an organization, it’s a community designed for physicians to connect, grow, and show up as their real selves. A place where professional development meets personal support. A place where the healer gets to be heard, understood, and known.

Let’s be honest: crossing that threshold into a new group for the first time is uncomfortable. I remember that feeling clearly in my own life—wondering if I’d fit in, if anyone would talk to me, or if I was interrupting some established circle.

But here’s the good news: once you step through the door, connection becomes possible.

Here are a few easy places to start with TCMS:

Join us at the TCMS Installation Dinner on Thursday, February 26th.

Come to the TCM Alliance “Party with a Purpose” in late March.

Watch a summer movie with us—low pressure, easy conversations.

But TCMS isn’t just about social events. It is a lifeline when life gets heavy and you need a little help recovering from your something.

If you’re struggling—whether with burnout, emotional strain, or addiction—our Physician Wellness Program and Physician Health and Rehabilitation Committee (PHRC) are here to walk with you. Quietly. Compassionately. And without judgment.

It all starts with one small action—replying to an email, signing up for dinner, raising your hand in a room where you don’t know everyone yet.

And while I’m at TCMS, I want you to know this: we’ll keep asking what you need, listening to your responses, and building a community that feels less like an institution and more like a home base for Austin physicians.

Because healing happens in community. And you deserve a community that supports your healing, too.

Troy Alexander, CAE

Executive Vice President/CEO – TCMS

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted February 2026

by Dr. Brian Sayers

Three Score and Ten

I turned seventy this week. Most years I do everything I can to ignore my birthday. I tried to do the same this year, but this time it made me pause and consider where I've been and where I hope to go. I have been blessed with a fantastic family, good health, and not too much to worry about. Like love and friendships, I look at my work through a different lens at this point in my life. It is now a privilege, even a pleasure most days to go to work, to be with patients I care about, colleagues I admire, and long-time staff at my office who I can count on. I hope to keep practicing for a few more years, and I will be sad to give it up.

It was the right time to reread Falling Upward by Richard Rohr as my birthday approached. The overall theme of the book is that there are two phases in life. In the first part, we are building and filling our “container.” The container is built and filled with things that we pursue through much of our lives ─ career, relationships, success, and a sense of identity and our place in this world. Importantly, it is also filled with what we accumulate and things that feed our ego. We often feel defined by how the world perceives us. He notes that in the second part of our life journey, we realize that much of what we have filled that container with needs to be emptied and replaced with things that lead to spiritual wholeness, self-discovery, and to lives lived authentically. It is a shift that we drift to, often without realizing it at first. It is time to focus more on things internal than external for the next, definitive phase of life. Life comes in the shape of an arc, he notes. We enter life with nothing but a divine spark. We travel through the wide world exploring, accumulating, finding love, learning from missteps and misfortune, often cluttering our lives with nonsense along the way. We abandon much of this later, now looking inward, hopefully discovering our true self as we return to our simple, sacred essence…and the arc is complete.

At the end of Elizabeth Stout’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel Olive Kitteridge, the main character looks back as she enters her later years, which have become surprisingly rich and full of love after years of loneliness and grief. She reflects on the great lessons she has learned, “…that love was not to be tossed away carelessly as if it were a tart on a platter…” and that at times when her life had been full of love, she “had flicked it off crumbs at a time ... because she had not known what one should know: that day after day was unconsciously squandered.”

Her lesson is a good one—obvious—but usually overlooked as we focus on the small things that fill our days. Each day is to be savored. I realize it more now than I used to. I love my family and my friends, my colleagues, and my patients. Always a little late to figure things out, I realize just how much I love life itself. And goodness… how I love my work.

Brian Sayers, MD

Associate Dean for Curriculum, Dell Medical School

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted January 2026

by Dr. Sherine Salib

Start with the End in Mind

“If a man knows not to which port he sails, no wind is favorable.” ~ Seneca, Stoic Philosopher

Starting with the end in mind is a powerful approach for any career, perhaps even more so for the fast-paced, hectic and ever-changing world of healthcare.

In an exercise used in some company and executive settings, and said to famously have been implemented by Warren Buffet, individuals are encouraged to take time to write their own obituary and then live it backwards. This same sentiment is highlighted in Stephen Covey’s celebrated book The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People— start with the end in mind.

Pausing and reflecting on how we want to be remembered, what our legacy will be when we—and others—look back at our years of work as physicians, is a powerful tool to remind us how we should live our day-to-day work today. This is a humbling and sobering perspective. It is a powerful tool that can help us reverse-engineer our choices and focus on the truly important everyday moments.

Our society tells us to focus inward, to compete, to climb, and to reach for more heights—whatever the cost might be. In the business of healthcare, the hectic pace of patient care, and the competitive nature of academia, this is a reminder to look outward—to focus on others, to contribute, to serve...to make a difference.

We are fortunate that our field of practice—that of medicine, with all its hustle and bustle—affords us more opportunities than most others to serve, and to make a difference.

So, I invite you today to pause with me. To reflect.

What is your personal mission, and how does that align with your day-to-day work in patient care?

When your career is over and you look back, what is the legacy you want to leave behind?

Will you, perhaps, be described as a lifelong learner, or someone whose greatest achievement was not necessarily the professional accolades and accomplishments, but rather the act of always showing up for others?

Will others remember your reputation for compassion and kindness?

What is your personal mission statement, and what are the values that guide that?

When all is said and done, what is the difference you want to make?

Clarity of destination gives every step its purpose.

“To begin with the end in mind means to start with a clear understanding of your destination. It means to know where you’re going so that you better understand where you are now and so that the steps you take are always in the right direction.” - Stephen R. Covey

Sherine Salib, MD, MRCP, FACP

Associate Dean for Curriculum, Dell Medical School

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted January 2026

by Dr. Richard DeBehnke

Welcome Home

Janus was the Roman god of beginnings and endings. He is often recalled at New Year’s, depicted with two faces looking forward and backward. He reflects on what has happened and peers into the future—not as a prophet, but to recognize the significance of transitions.

Last year, the TCMS Physician Wellness Program (PWP) faced its own transition. I want to recognize the hard work of our steering committee members in rising to the occasion and successfully sustaining this important program. Over the past twelve months, we were able to provide over 500 therapy sessions to more than 100 of our colleagues—visits that are anonymous and free.

Our fundraising efforts this year were quite successful, exceeding previous years by more than 18%. Our contributions came from diverse sources, as listed below. Donations from individuals accounted for one third of our total. This grassroots support from our peers is especially touching!

In 2026, we hope to build on our past success and to not only continue the Safe Harbor Counseling Program but grow and expand the role of the PWP in new ways. As we look to the future, we need your support to sustain and grow the program.

Support PWP by continuing the generous financial support that we have received in the past. When you renew your dues, please consider remembering us.

Be an ambassador for the program. Make yourself aware of the services that we offer and have the courage to be the one that reaches out to a colleague in distress, directing them to help.

Attend the CME events we sponsor—these events are all focused on improving physician well-being.

Read our blog weekly. Not only does it contain announcements of CME and other events, it contains our weekly essays. These essays come from you. The care and wisdom that are shared in these contributions are incredibly inspirational.

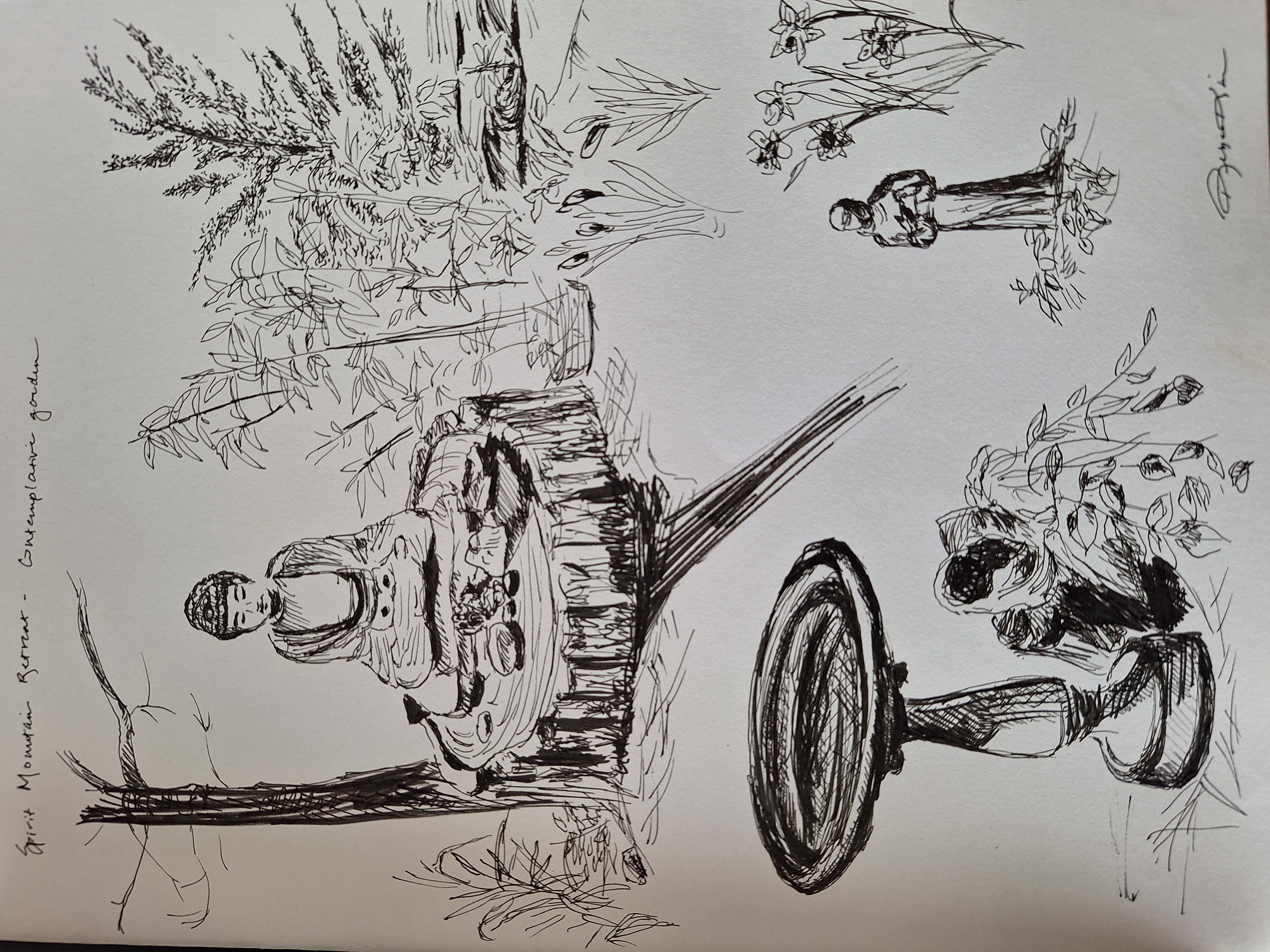

As well as reading the blog, please consider sharing your thoughts, concerns and insights with us in any medium you choose, whether it be written, drawn or sung. We all underestimate our ability to create and the impact that it can have on our peers.

Perhaps the most important way one can support our program is by utilizing it. I challenge all of you reading this to reflect on your training and your career. I believe that we can all find episodes in our lives where we would have benefited from counseling—sharing our anxiety and fears to become a more complete person.

Our profession is demanding but virtuous. It demands that we try to do the right thing because it is right and not for our personal gain. It helps us live well and find greater meaning in our lives. Our actions can inspire others and have ripple effects that make our community better. But, our profession also requires courage.

Author C.S. Lewis described courage as not one of the virtues, but the form of every virtue at the testing point. We are tested daily, whether by the rigors of our job or by inefficient EMRs, arbitrary metrics, prior authorizations or any of the dozens of hurdles we encounter.

We are the PWP. You are the PWP. And we are here for each other.

Richard DeBehnke, MD

PWP Steering Committee Chair

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted January 2026

by Dr. Blair Walker

Welcome Home

I have been in Travis County—and a member of the Travis County Medical Society—since I was an intern in 2009. At the time, our employer Seton and my Psychiatry Residency Program automatically signed us up every year as a benefit of our employment. It was always there for me, and I eventually started paying the annual dues on my own.

Just over a year ago, during my ninth year as an attending physician after five years in residency training, I received one of those renewal requests and checked some "I Have an Interest In..." boxes for the first time and—BAM! —I was on the Women in Medicine Committee. When I saw that an old buddy from residency, Dr. Holli Sadler, was the new Executive Board president, I figured I’d have a friendly face and checked the box for being an Alternate Delegate and—BAM! —I was signed up for that too! I was later asked—after they got to know me and understood my expertise in Psychiatry and Addiction Medicine—to join the Physician Health Rehabilitation Committee, supporting our colleagues in recovery from substance use disorders—which has been incredibly rewarding and meaningful.

I also heeded the "call to arms" last legislative session and after cajoling some other colleagues to join me, went up to the Capitol after work to testify about the "scope creep" concerns. We sat for several hours watching the dance of politics in the reverential environment of the Senate Chamber and learned from other physicians who clearly do it all of the time. It was fascinating and frankly really cool to be able to help educate our legislators, enacting change at the government level. I hope others will be inspired to get involved in the future, because it is an easy and highly organized First Tuesdays Program, with alerts from TCMS to participate in testimony throughout the session.

Now that I am more involved with TCMS, I can easily say that I feel much more connected to local doctors in our community from many different specialties other than my own, and that I now have a “home” at TCMS. The networking is incredible. At the Annual Awards Dinner, I shook hands with attendees who trained me and that I hadn’t seen in years, former residents I helped to train, and even colleagues whom I had never actually met in person but who I consulted on cases with at one time or another. I finally got to hug close colleagues whom I have spent texting or calling for months—and even years—of phone calls and texts. I recognized recent and past colleagues all over the room, similar to the Women in Medicine events that initially got me started with TCMS not so long ago. The smiles were genuine and the camaraderie real, making the Travis County community of doctors feel small given how many people I recognized, despite such a large region and growing number of physicians.

I write this account of my late start to TCMS involvement in the hopes that residents and early career physicians don’t wait as long. We need your passion and energy! TCMS is an incredibly welcoming and fun society to be a part of, so I hope you dip your toe in a little and get pulled in just like I did—and soon!

Welcome Home—to TCMS!!!

Blair Walker, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted December 2025

by Dr.Gabriel Millar

The Power to Heal

I have been in private practice in Pediatrics for almost 30 years now. My journey has not always been a smooth sail. The myriads of challenges—both personal and professional—were daunting but not insurmountable.

What helped me get through all of these is my faith in God, my wife and my sons, my parents, my extended family, my dearest friends—and my Art!

Growing up, I thought that one day I was going to be a successful artist, but I knew I did not possess that raw inherent talent. Thus, I settled with the next best thing!

Now, I have the best of both worlds. The work and career that I truly enjoy and the passion in art that I can indulge in without the burden and worry of critiques that artists dread.

I am preparing for my Board re-certification and to help me ease my worry, I read and review and paint in-between in my studio (a.k.a. our spare bedroom). To my surprise and delight, it helps me focus more.

Indeed, art has the power to heal, help me stay grounded, and boosts my self- confidence and self-esteem. I hope that I will be blessed in my retirement years with good health in mind body and spirit to continue painting and—maybe one day—exhibit my art!

Gabriel Millar, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted November 2025

by Dr. Lisa Savage

Keepsakes

Does anyone else have a folder or drawer at the office stuffed full of cards and letters from patients? Maybe these days it’s more likely to be a digital file but keeping a collection of thank you notes or other mementos from grateful patients is an easy way to bolster your confidence or serve as a reminder of the good that you are doing. It can also be a trip down memory lane that spans the arc of your career to remind you of how many patients you’ve taken care of, how far you’ve come as a physician, how many lives you’ve touched.

I had such a folder in the bottom drawer of my desk when I had my brick & mortar practice. When I was moving out of that office, emptying out my desk, I came across that messy, wrinkled and over-stuffed folder and got distracted from the task at hand by its contents. I was touched by how the busy women who were my patients (and a few of their husbands) took the time to write and send or bring me something I could hold in my hand, something I could save. Sometimes the cards contained a picture of their baby or toddler or teenager (!) whom I had delivered. Other times it was just a sweet note of thanks or remembrance. That folder sustained me on those occasional bad days we’ve all experienced when a patient was unhappy or wrote a negative online review. It can be so easy to fixate on one patient’s perspective or unmet expectations and forget about the hundreds of others whose gratitude you earned.

And wow, how the items in that folder grew when I sent out the letter to my patients announcing the closure of my in-person practice. Those alone needed a new folder! I ended up transferring all of it to something sturdier, one of those keepsake boxes you get at the hobby store, that I will continue to treasure and sit down with from time to time.

Two favorites stand out. One letter was from a husband whose wife had a stat C-section for fetal distress. I loved a good stat section, but this one was especially stressful. Afterward, with a good outcome, I went on with my day, week and month as usual. Around the time of the patient’s postpartum appointment, I received her husband’s letter, and in it he said I was brave. Brave! I had never thought of myself as brave, but seeing it through his eyes, I was both flattered and humbled. I know the entire L&D team looked like heroes to him, while we were just doing our job. But bravery is something each and every one of us physicians has, whether it is displayed dramatically or not. It takes courage to enter that exam room, wield that scalpel or sit with someone for whom you have little else to offer but your presence.

The other favorite was a completely unexpected note from a patient who wrote in sympathy and support when she heard about a trying medical practice experience I went through that had nothing to do with her. I keep that one separate, in my desk drawer at home. She has no idea what an impact she made on me, but in the midst of a difficult time in my career, she was kind enough to write. I saved her note as a welcome reminder that even in the midst of trials, there are many patients who sing our praises.

Keep those cards, print out the emails, make a folder; eventually you will need a keepsake box. At the end of a tough or extra busy day at work, take a few minutes with what’s in your collection. Sift through all that affirmation when you wonder if what you are doing is making a difference or feel the weight of balancing all your roles or want an alternative to perseverating about the Yelp review. It’s free and always available. Gratitude from our patients is common, of course, but when it is expressed in writing, you can hang onto it as a tangible reminder of how much you are valued and appreciated.

Lisa Savage, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted November 2025

by Dr. Sheila Shung

Tennis Saved Me

What gets me out of bed every day?

My husband and I have done a pretty good job of raising our two children. They are independent and well-adjusted young adults controlling their own destinies.

The daily household chaos is gone.

My work at my clinic for the past 23 years is routine—no catastrophic events, most of the time. My patients are well-known to me by now.

Life is now quiet and routine…but certainly not mundane.

After 4:30 p.m. on most weekdays (and even earlier on Friday!), I am a free bird. The first thought that comes to my mind when I open my eyes every morning: Who am I playing tennis with today? What? Laura again? The devilish tennis rabbit who runs me all over the court? Well, I better hustle and get ready!

Tennis saved me. It’s been five years since I first picked up a tennis racket, after the tennis courts opened up toward the end of the pandemic. Since then, I have met many women who are in the same boat as me, trying to relieve stress from a day’s work. I never imagined that I would become the captain of multiple tennis teams leading 40 to 60 mostly women players playing U.S. Tennis Association’s league matches every week. These women are my inspiration—most of them still have young children at home, with many more responsibilities than I, but give their best every week on the tennis courts. I have become the team mom. It is now a tennis sisterhood, celebrating life and supporting one another.

On rare days I can’t play tennis due to weather, I fall back on sewing and quilting. You would not believe I could sit for that long if you knew me! Quilting got me through the pandemic. After signing off from virtual patient visits every day, I cut big pieces of fabric into tiny pieces of fabric, then sewed them back into a big piece of quilt—a piece of art. Believe it or not, quilting preserved my sanity.

The quilters have a saying: "When life falls to pieces, make a quilt."

How does one balance the demands of work and life? Advice I give to my patients: do something for yourself every day. Even if it is for 15 minutes, do it! Whatever will make you happy for those 15 minutes, do it! You will be amazed at how much you will look forward to doing something that will make you happy, and how much it will help you get through your daily grind.

Looking at one of my physician friend’s photographs always make me smile. He took pictures of highways, wildflowers, hospitals at dawn, hospitals at sunset and whatever he saw that day. I bet that made him very happy. Sharing the pictures made me feel his joy.

When you wake up in the morning, before all of the chaos, responsibilities, demands, and text messages crush upon you, ask yourself: "what am I going to do for me today?

Sheila Shung, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted November 2025

by Dr.Tony Aventa

Keeping Your Balance

I do not believe myself to be an expert in physician wellness, but as a friend recently told me, "Wellness is not one size fits all."

As we strive towards meeting the challenge of increased work-life balance, not all of us will pursue art, poetry, or photography. During my early career, I enjoyed participating in triathlons, but nowadays playing pickleball with my wife and taking the occasional outdoor vacation have filled that role. Not surprisingly, in our current healthcare system developed on volume-based care, trying to achieve that work-life balance becomes more difficult. I have always worked towards passionately protecting my patient-physician relationships. It is one of the core beliefs that I take into the State Capitol when participating in First Tuesdays. It is hard to say how long the bonds of that relationship have been strained, but I suspect from our end increasing costs, regulations, need to see more patients, non-patient facing work, and the computer screens between me and my patient contribute to that stress.

I recently read an article by Dr. Lara Kunschner Ronan, a retired neurologist/neuro-oncologist, reflecting on her retirement process. She wrote, "Eventually it was time for me to move on, to leave the stress and the toll it was taking on my personal life and my ability to enjoy my job." She also reflected on her range of emotions through the process, including "relief, happiness, relaxation, but also a sense of betrayal, anger, and grief. The strangest emotion has been a persistent feeling of guilt." The passage that really hit home for me was "the physician identity development ingrained during my education and training had burrowed deeply into my psyche and is the little voice on my shoulder that even now continues to say, ‘You are selfish to prioritize yourself’.” Dr. Kunschner Ronan agrees that many patients and colleagues will be supportive of our personal decisions but writes, "many more will judge you for failure to uphold your tacit contract with society, for your lack of loyalty, for your personal failings and lack of resilience."

With many of these emotions swirling in me over the past year, I have investigated solutions to move from a volume-based care model to one that is more patient-centered. I am currently going through a bittersweet transition phase which I think will lead to a more fruitful continuation of my patient–physician relationship. I believe I will be getting back long-lost time to spend with my patients and really drill down to meet their needs. I will admit to you, my physician colleagues, that this pathway brings with it

many challenges for medicine as a whole, but I am unbelievably fortunate to have the support of my physician partners as I continue to practice in this new patient care model.

For me, the time to protect and prioritize my relationships with my patients is now. My hope is that this transition will also allow me the opportunity to more fully appreciate the life side of the work-life balance equation.

Tony Aventa, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted November 2025

by Dr. Nilanjana Dasgupta

The Symphony of Two Lives

The path to becoming a physician is often described as a marathon—a relentless test of endurance and focus. For a woman carving out her career, this journey is often a duet, the demanding melody of medicine intertwined with the powerful rhythm of family life. My own journey as a physician began as a long-held dream, but it truly found its unique harmony when I became a mother during my chief residency. Suddenly, the sterile walls of the hospital shared space with the vibrant, messy reality of home.

The years that followed were a joyous, breathless balancing act. My calendar became a testament to this duality: morning rounds ceded to afternoon soccer games, the gravity of a patient’s diagnosis was replaced by the lighthearted chatter of a parent-teacher meeting, and the precise measurements of pharmacology gave way to the comforting science of cookie baking with a cohort of other physician-moms. It was a life lived at full volume, a constant and beautiful tension between fulfilling my deepest professional ambition and embracing the transformative identity of motherhood.

As I look back now, it wasn't a Herculean effort that kept me from burning out; rather, it was the deliberate cultivation of four foundational pillars that instilled joy, excitement, and a profound sense of wellness to begin each day and look forward to work.

Pillar 1: The Anchor of Mission

Roughly a decade into my career, I experienced a powerful professional recalibration. I realized my deepest satisfaction was not a matter of prestige or pace, but mission. This connected me back to my medical school days—I trained at Mahatma Gandhi’s rural institution where prevention and community health were the key focus. Specifically, working within an FQHC (Federally Qualified Health Center) model focused on the senior population now gives me the most pleasure. This work is holistic, rooted in community, and fundamentally focused on dignity. Aligning my daily practice with a mission that speaks directly to my values provides an enduring sense of purpose that transcends the administrative burdens and emotional fatigue of healthcare.

Pillar 2: The Lifeline of Community

The second, and perhaps most vital, pillar is my "besties": a group of physician moms. This community is forged in the trenches of simultaneous professional and domestic urgency. They are the sounding board for an impossible patient case and the emergency contact when school pick-up clashes with a critical procedure. We lean on each other to vent, celebrate, and normalize the inherent chaos of our lives. This non-judgmental, mutual support system is a powerful buffer against isolation, acting as a crucial decompression chamber.

Pillar 3: The Dedicated Identity of a Mom

I learned that true balance isn't about perfectly merging two identities but about dedicating time and space to each one independently. I had to consciously commit to building an identity as a mother and a wife separate from my identity as a physician.

Leaning and connecting with other families while building a “circle” of friends who have become like family is invaluable. This has created a consistent deep-rooted sense of love and belonging for my children and me that we always carry with us.

When I am at social gatherings, celebrating a festival, or helping with a school project, my white coat is metaphorically left at the door. This mental boundary-setting allows me to be fully present in both roles, ensuring that I am recharged by the small, sacred moments of family life.

Pillar 4: The Freedom of Unburdened Time

Finally, I discovered the profound importance of carving out space to be simply me. For me, this sanctuary manifests in two hours a week of Bollywood dance. For those 120 minutes, I am neither a physician nor a mother. The weighty responsibilities of my primary roles dissolve. I am simply following rules and instructions related to steps, enjoying the music and the rhythm. This deliberate act of engaging in a non-essential, purely joyful activity is a vital cognitive reset. It is a moment where my mind is fully occupied with a task that has no life-or-death consequence, allowing me to return to my professional and maternal duties with renewed energy and perspective.

Wellness for the physician-mom is not a singular achievement, but a continuous act of intentional orchestration. It is the commitment to a mission that gives work meaning, the cultivation of a community that provides emotional ballast, the protection of family time that grounds the self, and the pursuit of unburdened joy that fuels the soul. It is this finely tuned symphony of responsibilities and retreats that ensures I greet each new day—and each new patient—with excitement, compassion, and resilience.

Nilanjana Dasgupta, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted October 2025

by Dr. Esther Yaniv

Inviting Forgiveness

Every Saturday morning, I forgo the luxury of sleeping in—something I feel I’ve rightfully earned after a long week. Instead, I find myself springing out of bed, energized by anticipation. While the streets remain quiet and free of traffic, I willingly make my way downtown to the yoga studio where I teach.

Teaching yoga became a gift I offered myself, without any idea of where it might lead or the lessons it would bring. After practicing yoga for several years, I was encouraged to join the teacher training program, primarily as a way to deepen my own experience. I had no initial intention of teaching.

In the early years of guiding classes, I was often critical of myself whenever I made mistakes. Missing a pose in the sequence or mixing up left and right would completely unsettle me. In those moments, I felt like a failure—ashamed and inadequate—yet each misstep became an essential part of my growth as a teacher. What I hadn't realized was that I was also evolving as a physician. The insights and challenges I encountered as a yoga instructor began to influence and strengthen my abilities in the medical field.

As a physician, vigilance against errors is paramount—mistakes can have serious, sometimes dire, consequences. The principle of "do no harm" perpetually underlies every medical decision, fueling questions like, “What if I miss something?” or “What if my diagnosis is wrong?” Over time, I recognized that this mindset had subtly permeated my approach to teaching yoga.

By drawing this connection, I began to see that mistakes need not be sources of relentless self-criticism. Instead, they can become opportunities to practice creativity, flexibility, and kindness. Mistakes invite forgiveness, humility, courage, honesty, and resilience. These qualities, cultivated on the mat, began to influence how I viewed both myself and my professional practice.

In a profession constantly challenged by bureaucracy and never-ending demands for efficiency, self-compassion becomes essential. While it is healthy to question and doubt—it keeps us sharp—there is little benefit in being relentlessly hard on ourselves in every facet of our work. What if we embraced humility not as a weakness, but as a strength in medicine?

My belief is that if we allowed ourselves this grace, we might find ourselves—like I do on Saturday mornings—leaping out of bed, ready and eager for the day ahead.

Esther Yaniv, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted October 2025

by Dr. Rebecca Kim

The Doctor as Artist

I have gone through different phases—figurative drawing, botanical illustration, animal paintings. There was a time that I did portraits of my pets, because they are such good friends and make me feel better no matter my worries or anxieties.

They each have unique personalities and their own little quirks. After one of my dogs died, I was glad that I had small remembrances of him later—even though it was poignant and bittersweet.

The little white dog is Sherman—he was full of charisma and personality. One dog trainer told me he was in my life to teach me not to be a doormat. He had a tan heart-shaped patch on his back.

The cat is Madeleine Grace, and I believe she is cat royalty.

The little chihuahua mix is Clementine. She is the opposite of Sherman - a bundle of nerves and anxiety and very vocal. She's a little chihuahua and needs to express herself!

There was also a time when I took a sabbatical several years ago to a tiny little city in California. I needed some respite and solitude after burnout, which can happen at different times in our lives. I rediscovered drawing to combat stress, doing some pen and ink drawings while wandering around. I met a writer there who encouraged me to find little vignettes and just start drawing.

Rebecca Kim, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted October 2025

by Dr.Brian Sayers

The Evening Star

On those rare evenings when I am sitting, undistracted, by a fire next to a pond at our weekend getaway in Fayette County, I become an amateur astronomer. Living in Austin, we see very little of the magnificence of stars on a clear night. Much like my identification of bird species on the property, I mostly fabricate the names of constellations and those around me either don’t mind or just ignore my babbling—but some things in the sky are unmistakable.

I’ve been considering the Evening Star recently, partly because of people we have lost in our medical community these last few months. Far brighter than other celestial bodies, the Evening Star shines low on the western horizon at dusk, just as, later, the Morning Star does on the eastern horizon with the approach of dawn. It is the visible manifestation of the orbital cycle that Venus travels: it shines as the Evening Star for 263 days before disappearing for 50 days, then reemerging as the Morning Star for 263 days before disappearing again.

Years ago, in another lifetime, I was an internal medicine resident in Albuquerque. New Mexico in general, and our patient population at County and the VA in particular, was a blend of direct descendants of the Spanish and the rich Native American heritage of the Navajo, Apache and other tribal cultures. In the mid-80’s when hospice care was in its infancy, it was not uncommon for patients to be hospitalized for terminal care at the VA. Alberto is one who I vividly remember. He had strong Mescalero roots and one evening his daughter recalled ancient legends about death, something I still think of when someone I care about dies. It involves the Evening Star and its endless cycles of darkness into light. According to some legends, the Evening Star is a celestial conduit, a spiritual guidepost that gently guides the deceased into the spiritual world, their eternal spirit eventually reemerging as the bright star in the east that heralds a new day. It is a legend that gives hope to the dying and those they leave behind.

We are a large medical community in Austin and most of you may be unaware that we have lost several of our colleagues these last few months, colleagues in the prime of their lives and medical careers, each death bringing with it shock and grief within their smaller communities. In church this morning our minister spoke of grief as a kind of exile, our return often accomplished with time and the help of community. Integral in the concept of community is a sense of belonging, a sense of shared concern, a sense of support. Our medical society has shown itself to be a caring, loving community. We accomplish many things—advocacy, community leadership, and support of local programs. But increasingly important, we are also called to support and care for each other in the many ways it is needed, and when it is needed most. The face of how that support is offered must adapt with the changing needs of our colleagues and circumstances of our profession, but the need for us to reach out, individually and collectively, is always there.

When I am sitting admiring the evening sky, I look for the Evening Star first, as it will disappear not long after dark. Finding something predictable is reassuring when so much around us is so unpredictable. My faith reassures me about death, and beyond, and that gives me comfort, but I also love Native American lore about the spiritual pathway of the Evening Star, of the hope and reassurance that the Morning Star is not far behind.

Brian Sayers, MD

Chair, Physician Health and Rehabilitation Committee

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted September 2025

by Dr. Holli Sadler

Networks of Kindness

For as long as I’ve been practicing medicine in Austin, I’ve had the privilege of working closely with local internal medicine residents. Residency is an intense and demanding time, but it’s also a period of profound growth and transformation. Watching the process unfold over three years—seeing a hesitant intern grow into a confident physician—has been one of the great joys of my professional life.

Because of my involvement in GME, my clinical practice has often taken non-traditional forms—shaped by community needs, time-limited opportunities, and very, very, limited budgets.

One of the most meaningful projects I’ve been a part of emerged several years ago, thanks to Dr. Lysbeth Miller, then-director of the residency program. She wanted graduating residents to experience home visits—not as medical providers, but as learners. We decided each resident would choose a patient they’d got to know well during training—either someone from their clinic panel or from frequent or prolonged hospitalizations—and, with the patient’s consent, visit them at home. The goal was to shift the lens: to interview patients not about medications or symptoms, but about their lives. We framed it with language about identifying social determinants of health and environmental barriers. But, at its heart, the project was about connection. It gave residents permission to slow down, to listen, and to reflect. And in doing so, it reminded all of us why we chose this profession.

The visits often surprised us. They revealed the extraordinary and quiet ways people survive and support one another. I remember homes that weren’t traditional houses at all—spaces patched together through networks of kindness. One patient lived in a converted shed, kept warm by a neighbor’s extension cord. Across town, a church group checked on a man every morning and if he was not in his expected location, they knew to call the hospital, then the jail—in that order. We went to houses where full families shared a single bedroom and the kitchen was a shared space, functioning like a cooperative.

These were not programs or policies. Rather, they were acts of trust and human kindness.

Over time, I came to think of those home visits as more than an educational tool. They sustained me. They filled my cup. I never left a visit without feeling a little more hopeful about the world. I learned about my peers—physicians in our community who quietly delivered high-quality, compassionate care to patients others might have overlooked.

Though the formal project has ended—the timing no longer quite right—I carry those experiences with me. They remind me that medicine is rooted in relationships. Even now, I can find moments to practice “slow medicine”—to pause, to witness, to honor the humanity.

We all have our own anchors in this work—those people, places, or rituals that remind us why we started and why we stay—patched together through our own networks of kindness.

Holli Sadler, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted September 2025

by Dr. Rchard DeBehnke

Hidden Heroes

Special moments often arrive unexpectedly and leave lasting impressions.

In my training as a resident on the hospital endocrine service, I was hastily checking on patients before morning rounds. The nurse alerted me that the lab for "Mrs. Y" was abnormal. I quickly reviewed it, glanced at her medical regimen, and hurriedly adjusted her medication…incorrectly. I moved on to check the other patients on the service, but before I could leave to start rounds with the attending physician, the nurse urgently called about Mrs. Y’s bedside glucose readings. I rushed back, saw what I had done, and made the necessary adjustments. Now late for rounds, the nurse who noticed the abnormal glucose readings informed me that the attending physician was in the break room and would like to see me.

My heart sank. My mistakes had been revealed. I was to be made a public example to hammer home a teaching point, something we all have experienced in our medical education—our own version of the public stocks.

I entered the breakroom and found the attending, "Dr. R," sitting alone.

“So, what happened with Mrs. Y this morning?” he asked. I told him that I had rushed through things, that I hadn’t taken the time the patient needed, and that I was mortified by what I’d done.

Dr. R stood up, straightened his jacket, looked at me, and said, “What can I say, Chief, you screwed up. Let’s go make rounds.” And with that, he walked out onto the ward. Stunned by the brevity of his confrontation, his familiarity, and his vulgarity, I quickly followed.

In an instant, Dr. R delivered a series of lessons:

He was disappointed but believed I was a better doctor than I had shown that morning, and he expected me to be that doctor moving on.

Owning your mistakes is the path to learning from them.

He had the grace and patience to know he was teaching humans and the idea of how to motivate them.

Sometimes what is left unsaid is more complete and powerful than what is said.

Richard DeBehnke, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted September 2025

by Dr. Vani Vallabhaneni

Yoga for One Earth, One Health

June 21st was the longest day of the year in the Northern Hemisphere. It was also “The International Day of Yoga,” recognized by the UN General Assembly in 2014, since yoga has significant health benefits. A total of 177 nations co-sponsored the resolution, which is the highest ever for any UNGA resolution, and was adopted unanimously.

Yoga originated in ancient India more than 5,000 years ago. The word “yoga” comes from Sanskrit root “yuj” meaning “to unite"—referring to union of body with mind, individual self with universal consciousness and breath with movement. When this union happens, we are able to connect more easily with our awareness, our inner self. We are able to use our intellect rather than relying on instincts. We can be more thoughtful and rational, responding instead of reacting.

Yoga practice is more than just stretching or exercise. It includes:

Physical postures (asanas) that help with stretching and strengthening the muscles and improving flexibility, range of motion, balance and posture.

Breathing techniques (pranayama) that help regulate our breath, improve lung capacity, calm the nervous system, and boost energy and focus.

Meditation & Mindfulness which help us take an inner journey and to be more self- aware. Meditation lowers cortisol level, increases endorphins, and reduces overall inflammation in the body. It trains the mind to be in the present moment, reduces stress and anxiety, and cultivates inner peace.

Ethical principles and Lifestyle (yamas & niyamas) which give guidelines for how to treat others and yourself with a foundation in values such as honesty, non-violence, self-discipline, and contentment.

With stress, anxiety, depression, and insomnia on the rise in modern society, it is more important than ever to practice yoga regularly and help our family and patients do the same. Deep breathing, yoga stretches, and meditation can decrease our stress response through reducing cortisol, and decreasing chronic stress can reduce burnout.

Anyone can stretch and deep breath comfortably in his/her own home as well as at work! It can be as simple as sitting back, closing your eyes, and taking a couple of deep breaths for one minute.

I routinely guide patients in my sleep medicine practice to explore yoga techniques by taking classes in their community or at their gym to improve their sleep. Meditation may be an effective behavioral intervention in the treatment of insomnia and can improve emotional well-being and mental health.

It is also a good practice to include a few minutes of yoga stretches, meditation, or deep breathing techniques at work before a meeting or before the start of the day. It can improve teamwork and decision making for the greater good of the organization. When leaders start their day with a practice of yoga and meditation, they can make better and more thoughtful decisions, and the organizations can thrive and be more successful.

My own practice of yoga started very early, as my school in India had yoga incorporated into PE class. I learned meditation and pranayama more recently and practice regularly. My favorite part of yoga is sun salutations. I find it very challenging to do some yoga asana and am still trying to master the sequence of moon salutations. I incorporate yoga into my life by joining group practice with my friends every Sunday morning and by being part of an online yoga community.

As you start your practice, go slowly and listen to your body. Use your breath to guide you into a yoga stretch. Learn under the guidance of an experienced and certified yoga instructor. Certain medical conditions such as heart disease or arthritis may require modification of your own program.

Yoga can be part of every physician’s wellness plan.

Vani Vallabhaneni, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted August 2025

by Dr. Jerry Fain

The Gift of Empathy

As a practicing hematologist/medical oncologist in Austin since 1996, I had seen firsthand how patients’ lives were changed in an instant from the diagnosis of a potentially life-threatening disease. However, it wasn’t until I was the patient that the full appreciation of the magnitude of such an illness became apparent. Although I was empathetic to the patients’ feelings, concerns and frustration, it never occurred to me that being a patient could change my practice as a physician. What transpired next was as life changing as the illness itself.

What started as a beautiful bike ride on a family multisport vacation in Jackson Hole, Wyoming early in the morning of July 21, 2014, would soon change in an instant. At the end of the ride there was an abrupt onset of sharp, stabbing, intermittent thoracic back pain with paresthesia in the back. I was having an acute anteroseptal MI. Fortunately, the decision was made to give TPA in the 2 bed ER in Jackson Hole and not wait to be transported by helicopter to the closest cardiac facility, a decision that no doubt saved my life. After a 4-day hospital stay, we returned to Austin and all was well until the morning of July 27, 2014, at 7 am when I experienced a v-fib arrest at home. Having a fire station 1 block away proved to be another blessing as the firemen were at our house within 2 minutes of the call. Having a physician spouse and an 18-year-old daughter who had just received BCLS certification at Westlake High School was another blessing. Five days later, after a defibrillator/pacemaker was placed, I returned home.

Upon returning to clinical practice, one of my long-term patients requested an appointment at the end of the workday. She wanted to be my last patient of the day, and it came as no surprise that she asked me to describe to her what had transpired during my 6-month absence from work. I had taken short term disability to recover. It soon became apparent that this appointment was not about her but about me. As a senior research scientist in Psychology at UT Austin, this patient had practiced clinical psychology for many years. She asked the open-ended question “and how are you doing now?” Without thinking, I described my inability to sleep since my discharge from the hospital August 1, 2014, due to pulsations in my ears and a bounding pulse. To me this was the physiological result from a reduced Ejection Fraction of 35%, and a previous MI; however, to a trained PhD in Psychology these were symptoms of anxiety, PTSD and possibly panic attacks. With her guidance I learned how to relax through deep breathing and guided meditation and, to my surprise, the pounding in my ears stopped.

Although the medical treatment had saved my life, it was the mental component of my illness that took me by surprise. Having validation that my symptoms were self-induced but treatable was very powerful and reassuring. So, from that day forward, whether it be a long-term patient or a new patient encounter, I took the time to ask my patients how they were coping with their illness. It became readily apparent that many of these patients with cancer were suffering from some form of PTSD and almost daily anxiety. I finally understood just how devastating cancer, or any potentially life-threating illness, could be. Patient after patient told me that the best thing that ever happened to me was having a heart attack, because I understood their angst, their fears and their thoughts because I had faced death and lived day to day with the 30%/year chance that I might suffer another cardiac arrest.

Now, some 11 years since that event, I still appreciate and recognize the psychological ramifications that illness of any kind can bring to a patient. Learning, it seems, can occur in any circumstance, and the events of July 21 and July 27 changed my life, my medical practice and every aspect of daily living. Although the panic attacks have resolved, the deep, dark memories and fears surface with each vacation, but with deep breathing and relaxation techniques provided by this special patient, I have lived another 11 years with some normalcy. My path to wellness included the skill of my doctors as well as an unexpected and timely gift from a very special patient.

Jerry Fain, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted August 2025

by Dr. Belda Zamora

Dr. Zamora and her father, Dr. Santiago Zamora

Finding Joy in Medicine

In our weekly physician wellness emails, one truth consistently shines through: each of us carries stories—moments and memories—that define who we are in this sacred calling.

I’ve been a family physician for over 25 years, a journey I began alongside my late father, Dr. Santiago Zamora. Today, I continue that path with my uncle, Dr. Pete Zamora, carrying forward a legacy rooted in service, compassion, and community.

There is a deep joy I find in caring for my patients and, often, their entire extended families. Over the years, these relationships evolve—we become witnesses to the births, illnesses, recoveries, and losses that shape their lives and ours. But with that honor comes weight. The privilege of walking with families through joy also means standing with them in grief. And when they suffer, we feel it too.

So how do I continue to find joy in medicine?

Most days, you’ll find me out on the trails—hiking, biking, or running in the Austin outdoors. Movement in nature offers me sacred space to reflect, grieve, and decompress. On lunch breaks, I often walk around Town Lake. Sometimes I go there to quietly mourn a patient I’ve lost, to process what I couldn’t in an exam room.

My greatest test came during the years I cared for my father—himself a pillar of family medicine in East Austin for more than four decades—as he navigated the painful decline of dementia. At the same time, my oldest son left for college out of state. I had to learn how to stop being the doctor and simply be a daughter. My days were a blur—rushing through patient appointments, squeezing in lunches with my father, and returning to the clinic, before ending my evenings with my two younger children at home. My weekends, too, disappeared into caregiving.

And yet, even then, joy would find a way in.

I was lucky to have a circle of strong, supportive women at my spin studio—our 5:30 a.m. crew. During this time, Belinda Clare (TCMS CEO) must’ve seen the fatigue in my face. She often encouraged me to reach out to the Physician Wellness Program (PWP) - but like so many of us, I kept saying I didn’t have the time. Still, their presence, their encouragement, their simple acknowledgment of the load I carried—that mattered. It reminded me I wasn’t alone.

Today, I still find joy in medicine. Despite the long hours, the emotional toll, the quiet heartbreaks—it’s still there. I believe the key to sustaining that joy lies in tending to ourselves, just as we tend to others. It’s in making space for grief, in choosing movement, in leaning into our communities—both professional and personal.

To those walking this road beside me: you are not alone. Your joy is not frivolous. It is necessary. And it is worth protecting.

Belda Zamora, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted August 2025

by Dr. Robert Duhaney

Me with the family at Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada - June 2025

Learning to Live Life Fully

A Physician's Story of Family, Faith, and Renewal

As a primary care physician and office medical director, I often find myself pulled in multiple directions—between patient care, administrative responsibilities, and the ever-evolving demands of modern medicine. But alongside this professional identity, I am a husband to my wonderful wife, Kelli, and a father to three vibrant teenagers. Learning to balance these two worlds—medicine and family—has been both my greatest challenge and greatest gift.

After completing my residency in internal medicine in Maryland in 2008, my wife and I relocated to Dallas, Texas, for my first position at a busy internal medicine clinic. I joined two experienced physicians who modeled deep dedication to their patients. Their work ethic was admirable, but over time, I noticed how often that commitment came at a personal cost. They seemed constantly stressed, and the strain of long hours and unrelenting patient care seeped into even the quiet moments of the day.

It didn’t take long for me to fall into that same rhythm—long clinic days, charting after dinner, answering messages late into the night. I told myself this was what it meant to be excellent. After we had our 3 kids and I continued trying out different practice set-ups over the past 12 years, I began to feel the toll—on my body, my spirit, and most of all, on my family. My children were growing up quickly, and I feared missing the moments that mattered. Though my marriage remained strong, it needed intentional time and shared joy to truly thrive. Something had to shift.

That shift started slowly but deliberately. Then the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted everything. Like many families, we found ourselves re-evaluating our lives. My wife and I looked at each other and asked, Is this our moment to reset? The answer was yes. I applied to a national primary care group—One Medical—that was opening a new location in Austin. After several interviews and much reflection, I accepted the offer, and we made the move in 2021.

Relocating gave us a fresh start. I began viewing this new chapter as a chance to double down on what mattered most: time with family, cultivating new friendships, and rediscovering joy outside of medicine. We made it a point to prioritize family dinners, show up at school events, and create simple weekend traditions like Saturday morning breakfast together.

I also rekindled one of my favorite pastimes: tennis. These days, my wife and I play regularly—sometimes attending clinics, other times just rallying for fun at an available court. It’s not just exercise. It’s laughter. It’s connection. We’ve even built friendships through tennis, meeting other couples for casual matches and post-game chats. These moments on the court have helped strengthen our marriage and brought a sense of play back into our busy lives.

Equally important has been staying rooted in our faith community. Our church has become more than a place of worship—it’s a place of belonging. Whether we’re facilitating small group gatherings, volunteering as a family, or enjoying meals with fellow church couples, these gatherings offer a spiritual reset and emotional grounding. They remind me why I chose internal medicine in the first place—to build long-term relationships, offer support in life’s toughest moments, and reflect compassion in action.

Saying “yes” to what fills me up—whether it’s quality time with Kelli, cheering on my kids at their activities, connecting with friends, participating in church events, or playing tennis—has helped me show up more fully for my patients and colleagues. I’ve learned that living with purpose doesn’t mean splitting myself into separate parts but integrating the roles I cherish most.

Finding balance doesn’t mean achieving perfect harmony every day. There are still weeks when inboxes overflow, the clinic is busy, and the pressures of leadership stretch thin. But I’ve come to believe that intentionality beats perfection. Each choice I make to align my time with my values brings me closer to the kind of wholeness I aspire to live out.

To my fellow physicians, I offer this encouragement: you don’t have to choose between a fulfilling career and a rich personal life. But you do have to be deliberate. Set boundaries. Protect your rest. Rediscover your passions. Lean into your community. These choices won’t just make you a better doctor—they’ll help you become a healthier, more joyful human being.

Medicine is a sacred calling, but so are marriage, parenting, friendship, and faith. When we give space to nurture all these callings together, we find not only balance—but true purpose and joy.

Robert Duhany, MD

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted July 2025

by Holli Sadler, MD

Ode to That Best Friend from Medical School

Take a moment and conjure up a memory of your best friend from medical school. Maybe you're in the thick of it now. Maybe, like me, it’s been so long you’ve stopped counting. Wherever you are in your journey, bring that person to the forefront of your mind. When did you meet them? What brought you together? When was the last time you had the chance to say hello? How big is your smile when they come to mind?

Her name is Tiffany. She’s from Tomball, Texas, and she remains one of my most treasured friends to this day—all thanks to the quiet foresight of a kind ophthalmologist named Dr. Spiegelman. Dr. Spiegelman taught the eye exam during our first semester. He had a calm, thoughtful presence and an unusual talent for seeing beyond the surface. One day, he pulled me aside and asked, “Holli, have you met Tiffany yet?” I responded that I had not. “She’s in another section of my class,” he said, “and I think you two would really get along.”

It was such a small moment, but I’ve never forgotten it. Dr. Spiegelman had a gentle, unhurried way about him. He noticed things—how people carried themselves, who looked like they needed a connection, who might be quietly drifting in a sea of over 200 classmates. In a place that could feel anonymous, his attention was rare. And it mattered.

I am, by nature, an introvert—a creature of habit who sits in the same spot, keeps to myself, leaves the minute the meeting has ended, and doesn't mind long stretches alone. I didn’t go out much in med school. I studied during the week so I could spend weekends with my husband. Tiffany and I didn’t share a lab group, an anatomy tank, or a clinical rotation. Our paths never directly crossed. Without Dr. Spiegelman’s nudge, it’s entirely possible we never would’ve met. But because he suggested it, I sought her out. I think I said something like, “Hi, I’m Holli. Dr. Spiegelman said we’d get along, so... let me know if you want to eat lunch together?"

That was it. Tiffany has been one of my dearest friends ever since.

It’s rare to meet someone who sees both your strengths and your chaos—who can make you laugh when you're unraveling and remind you of who you are when you’ve forgotten. That’s Tiffany for me. Any time I have a question that touches her specialty, I treat it as an excuse to call. When life gets hard—personally or professionally—she’s often the first person I reach out to. She’s spent long stretches on my couch. I went to Paris to be in her wedding. Her family feels like an extension of mine. She’s been there: for weddings, births, funerals—the full spectrum of life. She understands the pressure, the exhaustion, the desire to do good work and still have something left for yourself and your family at the end of the day.

After one especially demoralizing exam in med school, she called to check on me. I told her, “I feel like a delivery truck ran me over—then reversed for good measure. Let’s just say I’m humbled.” Thirty minutes later, there was a knock at my door. Tiff stood there holding a six-pack of Heineken and a bag of peanut M&Ms. That image of her—kindness in hand, mischief in her eyes—is etched in my memory forever.

In a profession that can be isolating and exhausting, friendships like that are rare and precious. I’m grateful every day that someone took the time to help me find mine.

Dr. Holli Sadler

tcms@tcms.com

Submitted July 2025

by Richard DeBehnke, MD

Regret

Regret is one of those words that carries a very negative connotation. The implication is that regret is a failing, a weakness that we should hide from others, and we should sail through life doing it “our way”. Reportedly, Frank Sinatra disliked his signature song, feeling it self-serving and insincere. In his book “The Power of Regret, How Looking Backward Moves Us Forward”, Daniel Pink agrees and proposes that a better understanding of the workings of regret will help us to make smarter decisions and bring greater meaning to our lives. Also, perhaps, make us healthier. His writing is entertaining, insightful and highly recommended.

In medicine, we are guaranteed to second guess ourselves on a daily basis. An ambivalent response to the regret of a less-than-ideal outcome can erode our self-confidence and our wellbeing. What struck me as I worked through Pink’s book were two things. First, understanding the nature of regret and its benefits could reduce the pressure that we put on ourselves and increase our joy of practicing medicine. Secondly, we rarely discuss regrets with patients during our history taking and doing so could provide additional avenues of therapy.

Whether a regret develops in an active (an argument with a spouse, lying) or passive (passing on a chance to take a new position, opportunities missed) way, it usually takes the form of “if only” or “what if”. Pink categorizes regret into moral failings, insufficient and excessive boldness (overwhelmingly the former), foundational decisions of picking short term pleasure over long term benefits, or loss of connections with friends and family due to rifts or just drifting apart. These categories provide a framework for us to examine ourselves and those we care for.

We all deal with our regrets in different ways. Far too often regrets are ignored or denied. This robs us of a chance to learn from our experiences and too often be consumed by the negative feelings regret generates. However, if we address regret, we can make better decisions, improve our performance by better deliberation, and find insight into ourselves and those around us. We can be catalyzed, not paralyzed.

This is where we as caregivers can find a dual purpose. Pink suggests ways of dealing with regret based on his own personal project, “The World Regret Survey”, a detailed questionnaire survey of over 26,000 people from around the world.

To summarize:

Undo it. “The best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago; the second-best time is tomorrow”. If possible, taking action now can help. If a door is truly closed, then be ready for the next one. If it is still open, then act now.

“At least” it. Find a silver lining. Interviewing medal winners at track meets and the Olympics, findings suggest that the bronze medalists were happier with their result than the silver medalists, by a lot. “At least” I got on the podium, versus “If only” I had trained harder.

Self-disclosure. Exploring one’s regrets is therapeutic. We are often inhibited by a reticence to “bother” someone, but humans are terrible about divining how others will react to their entreaties, overestimating their intrusiveness and underestimating the positive effects of any interaction. Engaging the involved party, journaling or talking with a caregiver can be rewarding.

Self-compassion. Ask them, “If your best friend had experienced or done what you had, what would you tell them?” Have them put distance in their perspective, “what would 2030 you, tell your 2025 version?”

Issues with regret are pervasive and can have health consequences, but we are well positioned to help ourselves and our patients. Thinking and asking about their regrets may be another channel in getting our patients to share what is affecting them and lead to alternative ways of therapy. Encouraging discussions of their regrets will build trust and provide a safe harbor for the discussion of feelings. “When feeling is for thinking and thinking is for doing, regret is for making ourselves better”. We would hope to provide them with the tools and perspective for making themselves better and avoiding being crushed by the weight of regret.

Dr. Richard DeBehnke

debehnker@gmail.com

Submitted June 2025

by Tina Philip, DO

The Road Ahead

It is hard to believe that we have reached the halfway point of the year. As you are all aware, there have been many changes within the Physician Wellness Program (PWP). Since I last wrote to you, a dedicated task force made up of our physician colleagues set out to find the best way to move the PWP forward after the retirement of Dr. Brian Sayers as PWP Chair. The end result was the appointment of a new Steering Committee to provide insight, direction, and inspiration and the creation of a TCMS staff position dedicated to supporting the program. I would like to give thanks to task force members Drs. Richard DeBehnke, Lisa Savage, Louis Robinette, and Maria Monge for the time that they spent thoughtfully working together to create this plan and our TCMS Foundation board for their approval to move forward.

The Steering Committee met for the first time this past Wednesday and it was a productive evening understanding the origin and many facets of the program. The committee will be responsible for overseeing the Safe Harbor Counseling Program, weekly physician wellness blog, continuing medical education, and future program development. It was wonderful to see how the wealth of experience in this group, coupled with a strong commitment to physician well-being, will undoubtedly move the program into the future. I would like to thank Drs. Richard DeBehnke and Sujata Jere for stepping up to lead this committee as chair and vice-chair.

To provide support to the Steering Committee and ensure that the program has the resources needed, Michael Warburton was brought on earlier this month as Physician Wellness Program Manager. Michael previously worked with TCMS affiliate organization, We Are Blood, as the Volunteer and Grants Manager. With a bachelor’s degree in communications and a Master of Arts degree in Counseling, he has worked within the Austin nonprofit arena for over 25 years. He has already hit the ground running and brought so much valuable insight and creativity, and we are so glad to have him with us.

Although there have been many recent changes, the mission of the Physician Wellness Program remains the same: to support physician well-being and foster a culture where physicians feel valued, supported, and empowered to maintain their own health and balance while delivering exceptional care. This program is for our physician family and we can all play a role in making it a success. We love to hear the many voices of our community, so please contribute to the program by sharing a creative piece for our weekly blog and encouraging your colleagues to do so as well. The Physician Wellness Program also relies on the generosity of our donors, so consider making a monetary donation at the link below. Thank you to our physician members for your continued support. I look forward to seeing all that we can accomplish together.

PWP Steering Committee:

Dr. Tina Philip

tina.philip@gmail.com

Submitted June 2025

by Bob Emmick, MD

Carpe Diem

Everyone knows what free advice is worth these days, but I will attempt to offer something valuable in 600 words or less. First though, I must admit that we are privileged to practice the best profession in the world, in my opinion, and if someone has reached the point that they absolutely dread getting out of bed and going in to see their patients, I would seriously recommend professional help, changing professions, or retiring. People can debate whether we should feel joy in our profession, but satisfaction in listening to and helping our patients I believe is attainable every day.

Here is my advice. It is useful to have goals, but we should experience life to its fullest both in our profession and when we are at leisure, recharging our batteries. I will focus on the leisure side of life when we are seeking peace and joy, that period of recharging, but the thought process can be applied to our professional lives as well. I do not believe in the concept of bucket lists, nor the use of rankings that one thing is better than all others. Instead, I believe that life is to be experienced to its fullest and that each experience can be appreciated for what it offers.

As I understand it, the concept of the “bucket list” is to experience something once then check it off before moving onto the next experience on said list. There is a basic flaw in this, in that no two experiences of the same thing are alike. As an example, I would suggest the eruption of “Old Faithful” in Yellowstone. You cannot compare watching Old Faithful at sunset, in the middle of winter with snow covering the base, or late at night with stars and the moon in the background when no one else is around. A second example slightly to the south of Old Faithful is sunrise at Oxbow Bend in the Grand Tetons. Is it best seen in the spring when you may have a bear or moose swimming across the Snake River, or in the fall when the leaves have changed their color? I dislike the “one and done” approach because you have deprived yourself of the other opportunities. Seek out the experience and appreciate what it offers, multiple times if possible.

Focus on appreciating the experiences and not trying to rank them in order of the best and those that follow behind. During my first year of medical school a group of us went to Cozumel on Christmas break. There we went to dinner at Carlos and Charlies. On the wall was a set of “Rules.” I do not remember the others, but I will not forget the first. It said,”1. You are on vacation so eat something that you do not eat at home.” That has stuck with me, and I have expanded it into the concept of not ranking experiences but trying to savor as many as possible. Should you try to rank the best meal or trip or sunrise or sunset that you have experienced? Can they be ranked, and if so, why? I suggest that we should seek out the experience and enjoy it for what it is. Then savor the memory that will recharge your batteries in the future, not whether it was a check on your “bucket list” or number 1.

I hope that this perspective has helped someone other than myself. In the end it can be summed up in just two words, Carpe Diem!

Dr. Bob Emmick

remmick1963@yahoo.com

Submitted June 2025

by Louis Robinett, MD

Sunsets and Sonship

In April of this year, my wife, 15-month-old son, and I took a trip to the East Coast for a long weekend to visit friends. This was my son’s first flight in a while, and I recognized that this might be a special moment for us. He held my finger while we walked around the terminal, quickly finding a window with a great view of parked and taxiing airplanes with the assortment of utility vehicles that serve them. He must have stared out for 15 minutes – an eternity for a toddler – watching the busy workers, tiny carts, and giant airplanes zip back and forth on the tarmac.

When we boarded our flight, I was sure to pick a window seat for us, and my wife snapped this photograph of our view after takeoff – sharp, ruffled edges of a large cloud brilliantly illuminated by the setting sun behind it. I remembered my first memories of flying, my own father doing the same thing to make sure that I had a front-row seat to the same spectacle.

But what does this beauty mean to a 15-month-old? My son has so far lived an innocent, healthy life devoid of major trauma or chronic health issues. Though many circumstances are beyond my control, it is among the greatest privileges as a father to provide stability and safety as my son grows and develops. Right now, he knows that the stove makes tasty food, but not that it can burn him. He knows that playing with the garden hose in our backyard is his favorite thing, but not that it’s contingent on next month’s mortgage payment. And I don’t want him to know that the plane he is in might crash, or that the ticket was expensive – I just want him to experience the wonder of viewing a sunset from 30,000 feet. The joys are for today, the burdens for another time.

I moved my face next to my son’s in the window because I, too, wanted to take in the weight of this moment. In the days leading up to our vacation, I was burdened with thoughts of my practice, my finances, my marriage, the hours of sleep I didn’t get the night before, my patients, not to mention the pile of notes that I brought with me from the week prior. What does this sunset mean to me, a middle-aged physician and father? Gazing at the magnificent scene, I couldn’t help but feel that all these difficulties were less important compared to the greater beauty that I was witnessing.

Maybe there are burdens that I, too, am being spared for now, ones that are for the future and not for today. I’m old enough to know that the stove can burn me and that my practice can financially fail. But there are also many more mistakes to make or mishaps to suffer in my lifetime that I have yet to experience, many that I never will. Tomorrow morning, the sun will rise again. Dew will be on the grass, bright red cardinals will roost in my red oak tree, the sky will be blue, and a breeze will occasionally ring my wind chime. Friends and family will still joyfully pick up the phone when I text or call. Spring will follow winter. Morning will follow night. Joy will follow despair. The brilliant cloud commands my attention to this.

And as I gaze back to my left, my son’s feet against my legs while he rests his head in his mother’s lap, I am filled with gratitude and thankfulness. I will carry these burdens with joy and grace. For today, the sunset is enough.

Perhaps, a humbling display of love from a caring Father.

Louis Robinett, MD

lrobinett@rheumtx.com

Submitted June 2025

by Lee Frierson-Stroud, MD

Music-the Soul’s Healer